He’s Just Not That Into You!

- Jeanette Luna

- Dec 18, 2023

- 12 min read

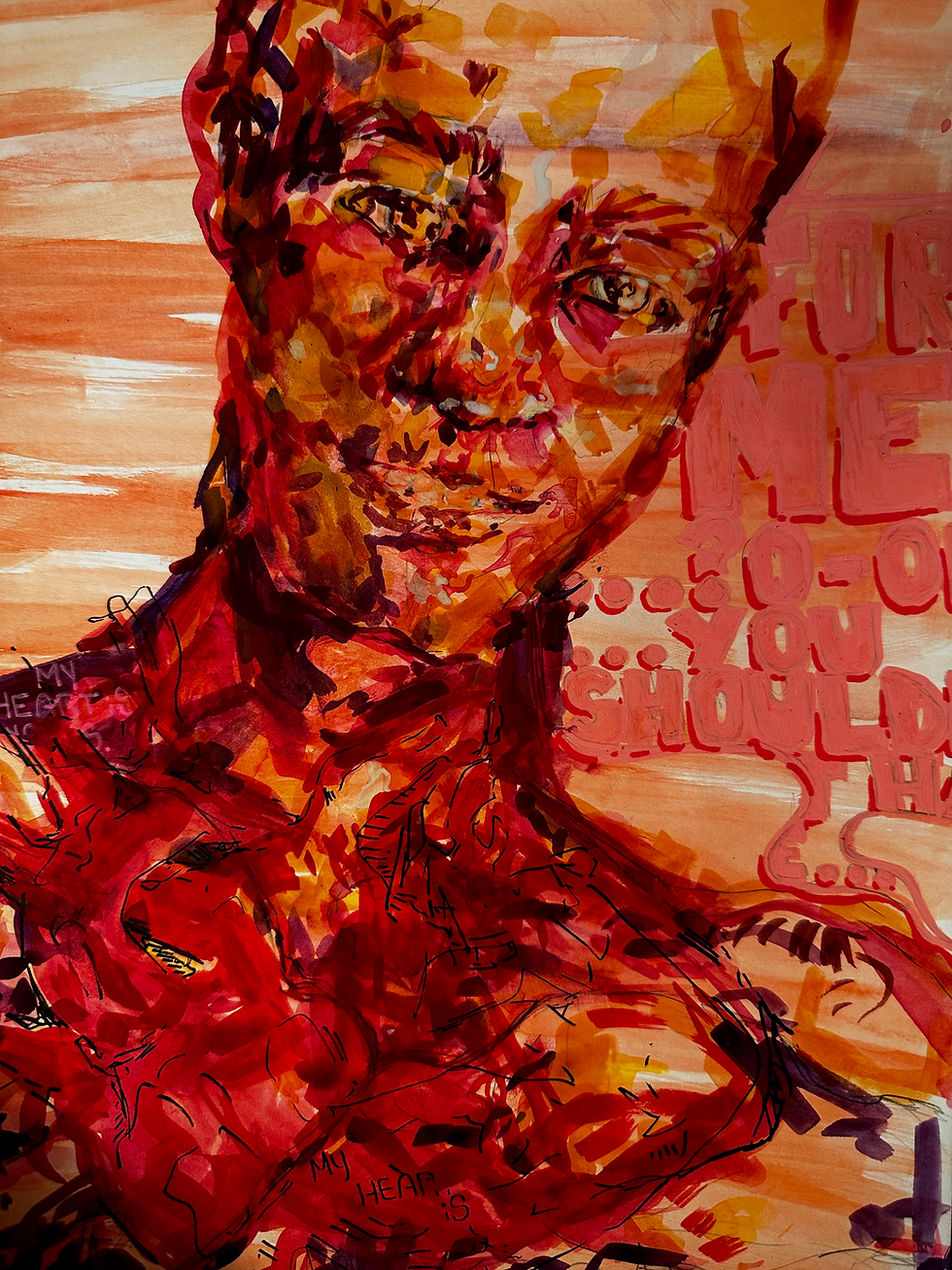

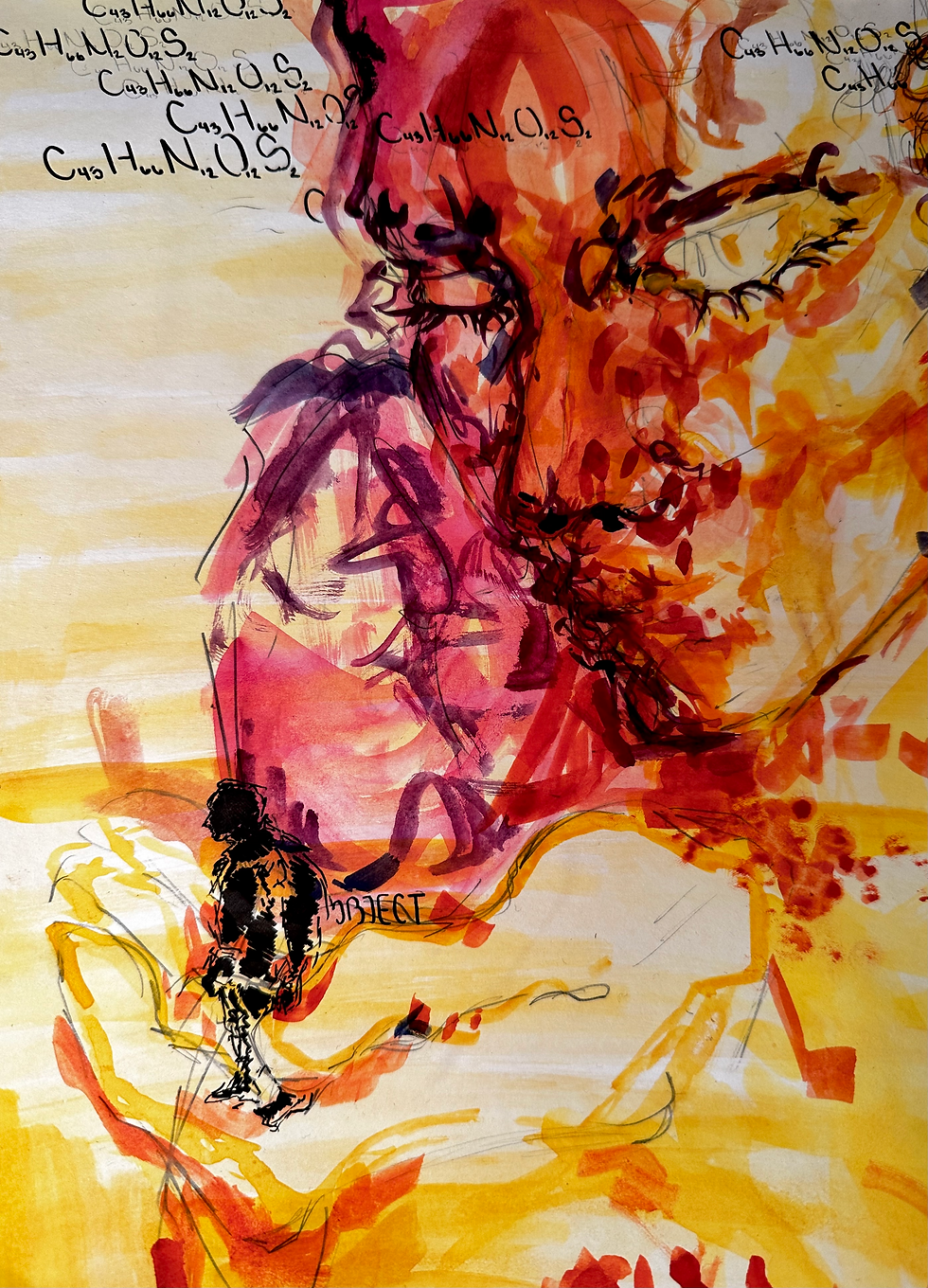

by Jessica Reschny

art by Sydney Eze

If you were to flip through the radio, what are the chances you would land on a love song? Spoiler: they’re probably just as high as the chances of your gossip sessions turning into love confessions or your TikTok ‘For You Page’ being infested with tarot card readings assuring you that your crush likes you back (or maybe that’s just me). Perhaps you land on a love song from the 60s that you don’t really relate to, and maybe you’re only listening because it’s an old lover’s favorite song, but passionate expressions of love in art and media have withstood the test of time because we just want to love and be loved.

Love follows us everywhere, whether that be the emotional flashbacks you get when you see a past lover’s name on a street sign, or when they pop into your head everytime you hear that favorite song of theirs. Infatuation can make us feel mad, but as Nietzsche once said about love, “there is reason in [this] madness” that can be revealed by chemical processes in the brain.

What is Limerence?

“I am in love with her, it’s not like last time!” you insist as you try to articulate how your crush makes you feel a way nobody has before—but isn’t this what you said last time? The term ‘love’ has been stretched to fit a diverse spectrum of situations and emotions- ranging from pure attraction to those complicated on-and-off relationships- that it lacks a precise meaning. Psychologist Dorothy Tennov interviewed over 300 people about manifestations of ‘love’ in their lives to gauge what people truly mean when they claim to be in love [1]. In her 1979 book, Love and Limerence: the Experience of Being in Love, Tennov classified common emotions and experiences as a state she termed “limerence,” described as “an involuntary interpersonal state that involves an acute longing for emotional reciprocation, obsessive-compulsive thoughts, feelings, and behaviors, and emotional dependence on another person” [1].

According to Tennov, limerence exists between a limerent person and their “limerent object” (LO), the focus of their attention. An LO can be a current or prospective partner, or simply an infatuation gone too far [1]. It can be difficult to pinpoint limerence in people “in love”, but Tennov noted that, unlike a person in love, a limerent person’s feelings and hope for emotional reciprocation are increased when their LO’s feelings towards them are unclear. When a limerent person doubts their LO’s feelings, they begin spending more time overanalyzing possible signs of reciprocation, along with appearing or acting in ways to impress them [1].

Limerence is not a diagnostic condition in the most recent edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (DSM-5), a handbook used to guide diagnosis of mental disorders. Adding a diagnosis to the DSM requires intensive research to ensure that the diagnostic criteria is precise and accurate to the condition [2]. Limerence research is very limited, especially to the demographic of heterosexual

women and men, so the definition of limerence is still too subjective to be classified as a disorder. So, when (if ever) do limerent behaviors become problematic?

Limerence as a Cycle

The line between having a harmless crush and showing signs of limerence is up to you to determine based on factors such as how much time you spend ruminating over your LO and how your quality of life is impacted. The emotional and behavioral ‘symptoms’ that Tennov originally classified as limerent manifest as a seemingly inescapable cycle, and researchers categorized these symptoms into three distinct cyclic phases: initiating forces, driving forces, and resultant forces [3].

According to this Wakin-Vo I.D.R. Model of Limerence, the initiating force is a combination of a pre-existing longing for emotional reciprocation, paired with an initial attraction to the individual that will become the LO [3, 4]. Tennov notes that this attraction feels like euphoria and, in the words of one of her subjects, “ecstasy” [1]. The memorable moment of the first interaction between a limerent person and their LO is often described as love at first sight, and it can (and certainly will) be replayed again and again; the look in his eyes when your eyes first locked had a glare you’ve never seen before, that must mean it’s love… right?

The driving force that fuels a limerent person is their doubt that the LO feels the same way, paired with a gnawing hope of reciprocation [3]. In spite of the LO’s indifference, you may obsessively read between the lines of their actions in search of clues of reciprocation, but avoid putting yourself in situations where they can reject your advances and diminish your hopeful fantasy. This is why you find yourself reading into every text, every little conversation, and overanalyzing every gesture, but not directly expressing your feelings or asking them how they feel. You find that each time you do these things, you discover a new clue that they’re into you and you get to relive the thrill of the initiating force, while also fueling ‘the chase’ (everybody’s favorite!) for reciprocation.

This thrill can quickly spiral into intrusive obsession, as if your default thoughts are about your LO and your mood depends on your perceived closeness to them [3]. The wide range of emotions, from ecstasy to depression and irritability, are referred to as resulting forces. You may feel on top of the world when you feel connected to the LO, but feel anxious, lonely, or shameful when you realize that you don’t know the LO’s feelings, and it’s possible that they aren’t that into you. Your self concept is the immediate target of limerence, as if you start seeing yourself through their eyes, but their glasses are always foggy. These hopeless feelings only motivate a limerent person to search for more signs of reciprocation, and the cycle repeats [3].

Love on the Brain

Well, it’s 2 A.M., and you’re aching to sleep, but your eyes are glued to your crush’s social media yet again (maybe even the people they follow on Instagram, as if anything has changed since your last time checking). You snap into reality when you realize you don’t even want to be stuck in the exhausting cycle of missing this person, and you begin to wonder why you’re so obsessed with them.

There is typically negative stigma associated with the term “obsessive,” but these types of behaviors can be products of the activity of your brain’s chemicals, such as serotonin [5]. Serotonin is a chemical messenger in the brain that helps regulate many crucial physiological functions, but is most famously known for stabilizing mood and impulsivity. Studies show that low levels of serotonin are correlated with various psychiatric disorders, including Obsessive Compulsive Disorder (OCD) [5]. According to the DSM-5, the symptoms of OCD can be split into obsessions, which are “recurrent and persistent thoughts, urges, or images,” and compulsions, which are ritualistic behaviors that an “individual feels driven to perform” [2].

Although limerence is not a diagnosable condition, many of its symptoms can be fit into the two categories of OCD symptoms. A notable characteristic of limerence is that it is very time consuming, both in terms of thoughts (much like obsession) and unwanted behaviors (compulsions) that aim to maintain closeness with the LO [4]. For example, one case study on a limerent person reported spending 30-90 minutes a day ruminating over past experiences with her LO, stalking his social media, and looking for ways to bring him up in conversation, which caused her to have mood swings and difficulties focusing. She was treated with cognitive behavioral therapy techniques that are often used for patients with OCD. Her treatment specifically focused on working on resisting compulsive behaviors, reframing irrational thoughts that put the LO on a pedestal, and filling her time with healthy activities such as socializing or exercising. Within the first 2 weeks of therapy, the time she spent thinking about her LO decreased to just 10 minutes a day [4]. The similar symptoms and treatment methods of OCD and limerence raise curiosity around possible neurochemical similarities between these conditions.

Research has been conducted to determine if limerent people have low serotonin levels, comparable to those with OCD. To do this, blood samples were taken because, although serotonin levels in the brain cannot be measured directly, the presence of serotonin in the blood can, and it’s correlated with brain serotonin levels. Blood samples containing serotonin were taken from two groups: those in love versus those who are not [6]. This study found that female participants in love displayed higher levels of serotonin, coupled with reports of obsessive thought patterns [6]. Although the relationship between love and serotonin calls for more up-to-date and diverse research, the behavioral and proposed neurochemical similarities between OCD and limerence suggest that limerence, like OCD, is correlated with irregular neural activity.

In addition to obsessive behaviors, you may reach a point where you feel inexplicably loyal to a crush, like you’re incapable of even looking at somebody else. Oxytocin—a hormone associated with maternal bonding, social bonding, attachment, and sex—may be to blame [7]. Oxytocin has been shown to be involved in rodent pair-bonding and mating, and there is an emerging field of research on oxytocin’s role in romantic attachment. A study was done collecting blood samples from people in new relationships versus single people, and oxytocin blood levels were higher in lovers who just entered a relationship than single individuals [7]. This means that higher levels of oxytocin are correlated with the original romantic spark that starts your love affair, and the attachment that maintains it. Further research focuses on the selective aspect of attachment that causes you to want to be loyal to one person. A study gave participants a nasal spray that temporarily increases oxytocin levels in the brain to determine how oxytocin levels affect participants’ attraction to strangers [8]. It was found that participants’ attraction to strangers was significantly reduced when oxytocin levels were raised, although their attraction to their partners was not affected [8]. Thus, higher oxytocin levels are involved with selective attachment, which is why you may feel bound to that one person, even when the infatuation fades.

Your Love is My Drug

Okay, you’ve established that you don’t even want to be keeping up with your crush anymore, so why do you always want to stay in the loop of what they’re doing? Even when you tell your friends you’re over them, you still get a rush when you are in contact with them or even just daydream of seeing them again.

In art, literature, and day-to-day life, addiction is often used as a metaphor for love, but is there truth to this? What are the behavioral and neurochemical patterns implicated in addiction and how do they compare to those of limerence? Though addiction is most commonly associated with substance use, behavioral addictions- such as gambling disorder and internet gaming disorder- have recently been included in the ‘Substance-Related and Addictive Disorders’ section of the DSM-5 [2]. Listed symptoms include pre-occupation, tolerance, withdrawal symptoms (irritability and mood swings), engaging in certain behavior to escape problems or feelings, and losing opportunities because of that

behavior [2]. These symptoms sound quite familiar to limerence symptoms, especially the cycle outlined by the Wakin-Vo I.D.R. model— a seemingly euphoric honeymoon phase spirals into intense cravings for that initial infatuation you’ve grown tolerant to, preoccupations thinking about ways to keep the LO close, and mood fluctuations when you feel you’ve lost that rush [3].

An underlying root of addiction is an overactive reward system in the brain. The reward system is responsible for processing the pleasures associated with certain behaviors or substances, and it largely depends on the presence of dopamine, a “feel good” chemical messenger responsible for pleasure and satisfaction [9]. When this pathway is activated, dopamine is released from the ventral tegmental area (VTA), a bundle of neurons in one of the brain’s most primitive parts which mediates reward, and sent to the nucleus accumbens (NAcc), an area of the brain that mediates your behaviors based on expected rewards [10]. When the rewarding experience ends and the dopamine release into the NAcc ceases, the individual is motivated to repeat the action that created those pleasurable experiences [9].

Much research has been done on the reward system in relation to love, which can be applied to underscore the behavioral and possible neurochemical parallels between those with behavioral addictions and limerence, a specific manifestation of love. Acevedo et. al conducted a study using imaging techniques to report brain activity of 10 women and 7 men who were “in love” when they were exposed to a picture of their romantic interests compared to when they were exposed to a picture of neutral acquaintances [11]. The central finding of this study was that there was increased activation in the NAcc and the right side of the VTA after being shown the romantic interest image versus the neutral image, the areas related with goal-directed reward circuitry in the brain and addiction. This supports prior research showing increased activation in the right side of the VTA when subjects saw a face they wanted to see for longer. The reward pathway activity was consistent between subjects, regardless of factors such as the self-reported intensity of the love or relationship duration, which ranged from 1 month to 17 months [11]. It is, thus, quite possible that reward system activity associated with addictions is similar in limerent behavior, which is why it is so difficult to abandon these behaviors. For instance, you may feel the effects of this pathway when you spend time reading old texts with your LO to relive the bliss you felt when you were in contact with them. This becomes pathological when the stimulus is inherently harmful or your quality of life has declined as a result, such as losing opportunities for personal growth or simply wasting time indulging in these chemically pleasurable behaviors.

Addiction is a heavily stigmatized term that is typically used for blatantly harmful behaviors and substances, but research has supported that behavioral addictions can root from innately harmless behavior. The biological basis of love in the reward system is similar to that in animals: releases of dopamine in response to interactions with a potential mate reinforce these interactions in order to increase likelihood of reproduction [12]. Animal studies found that female prairie voles have a 50% increase in dopamine in the NAcc when mated with a male; when given a substance to reduce the brain’s reaction to dopamine, the prairie vole would no longer attach to that mate [12]. Thus, processes in the reward system associated with love are part of our evolutionary mating mechanism, and they are absolutely crucial to sustaining life. Dopamine’s role in the reward system is not inherently harmful (love is beautiful!), but can become an issue when you feel like it’s controlling you.

So Sick of Love Songs

If you’ve made it this far, you probably feel quite called out, but (hopefully) equally as seen and supported. You finally have a name for that obsessive crush you feel nobody else understands and, at times, you don't even quite understand. It turns out that romantic connection is grounded in the brain’s chemicals and pathways, and the obsessive nature of limerence is likely associated with the imbalance of this activity rather than some kind of moral shortcoming on your part. Love is one of the most beautiful parts of being human and, even when it takes the form of limerence, it’s still part of having a human brain! Pinning this seemingly mystical feeling down is the first step to regaining control of your mind, and you now have the opportunity to wipe your eyes and see your situation (and yourself) clearly. With time, your limerent behaviors may bind you to a mental cycle of “what-ifs” about your LO, and the narrative you created to answer these questions. You can break this cycle by unraveling behavioral patterns that do not serve you, and it may be beneficial to talk to people you are comfortable with so they can offer a fresh outlook on the feelings you have sat with for so long. Whether you are daydreaming of your past or future with your LO when you hear their favorite song, turn down the volume and surrender to the joys you’re experiencing in this present moment, even (and especially) in their absence.

REFERENCES:

2. Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders: DSM-5. (2013) (5th ed.). Washington: American psychiatric association.

3. Wakin, A., & Vo, D. (2008). Love-Variant: The Wakin-Vo I. D. R. Model of Limerence. Psychology Faculty Publications. Retrieved from https://digitalcommons.sacredheart.edu/psych_fac/131

4. Wyant, B. E. (2021). Treatment of Limerence Using a Cognitive Behavioral Approach: A Case Study. Journal of Patient Experience, 8, 23743735211060812. https://doi.org/10.1177/23743735211060812

5. Pourhamzeh, M., Moravej, F. G., Arabi, M., Shahriari, E., Mehrabi, S., Ward, R., … Joghataei, M. T. (2022). The Roles of Serotonin in Neuropsychiatric Disorders. Cellular and Molecular Neurobiology, 42(6), 1671–1692. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10571-021-01064-9

6. Langeslag, S. J. E., van der Veen, F. M., & Fekkes, D. (2012). Blood levels of serotonin are differentially affected by romantic love in men and women. Journal of Psychophysiology, 26(2), 92–98. https://doi.org/10.1027/0269-8803/a000071

7. Schneiderman, I., Zagoory-Sharon, O., Leckman, J. F., & Feldman, R. (2012). Oxytocin during the initial stages of romantic attachment: Relations to couples’ interactive reciprocity. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 37(8), 1277–1285. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2011.12.021

8. Freeman, H., Scholl, J. L., AnisAbdellatif, M., Gnimpieba, E., Forster, G. L., & Jacob, S. (2021). I only have eyes for you: Oxytocin administration supports romantic attachment formation through diminished interest in close others and strangers. Psychoneuroendocrinology, 134, 105415. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.psyneuen.2021.105415

9. Cooper, S., Robison, A. J., & Mazei-Robison, M. S. (2017). Reward Circuitry in Addiction. Neurotherapeutics, 14(3), 687–697. https://doi.org/10.1007/s13311-017-0525-z

10. Lewis, R. G., Florio, E., Punzo, D., & Borrelli, E. (2021). The Brain’s Reward System in Health and Disease. Advances in experimental medicine and biology, 1344, 57–69. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-030-81147-1_4

Comments